Volcanoes mobilize carbon: New studies upend climate narratives with 3X CO² estimate and 19,000 new undersea peaks

05/21/2025 / By Willow Tohi

- Advanced sensors revealed that volcanic CO? emissions—particularly from overlooked cooler hydrothermal zones—are up to three times higher than previous estimates, though still dwarfed by human fossil fuel emissions (~5% of total).

- Satellite radar data identified 19,325 previously unknown seamounts (submerged volcanoes), suggesting these “carbon actors” may influence ocean heat/carbon cycling, though their total impact remains unquantified.

- The studies expose critical uncertainties in natural CO? contributions, challenging the 90% anthropogenic attribution of modern atmospheric CO? increases and urging recalibration of climate models.

- High-sensitivity sensors and drone/satellite tools are revolutionizing volcanic monitoring and seafloor mapping, improving eruption forecasting and highlighting the need for global initiatives like Seabed 2030.

- The findings underscore the complexity of Earth’s carbon cycle, demanding humility in climate science and a reevaluation of mitigation strategies to account for previously overlooked natural processes.

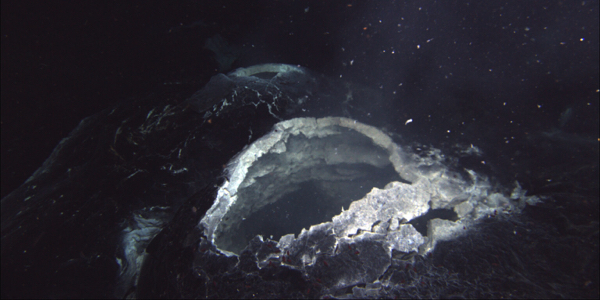

Two groundbreaking studies have reshaped our understanding of Earth’s carbon cycle, casting doubt on long-held assumptions about natural versus human-driven carbon emissions. Researchers from the University of Manchester and the University of Hawaii’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) uncovered that volcanic CO? emissions are three times higher than previously estimated, while simultaneously discovering nearly 20,000 unknown undersea volcanoes. Published within weeks of each other, these findings challenge climate models and highlight critical gaps in assessing natural CO? contributions to the atmosphere, all while raising urgent calls for re-examining the drivers of global warming.

Volcanic emissions redefined: Triple the carbon

A team led by Alexander Riddell at the University of Manchester deployed advanced sensors on helicopters to measure emissions from Montserrat’s Soufrière Hills Volcano, a site riddled with both hot fumaroles and cooler hydrothermal systems. The study, published in Science Advances, revealed the volcano releases up to three times more CO? than earlier estimates.

Traditional monitoring focused on gas-rich fumaroles, overlooking cooler zones where water absorbs acidic gases like sulfur dioxide (SO?) and hydrogen chloride (HCl), leaving CO? emissions undercounted. Riddell emphasized, “Volcanoes play a crucial role in the Earth’s carbon cycle,” but stressed that even tripled emissions still place volcanoes at less than 5% of global CO? output compared to human activities. Yet, if this multiplier applies to other volcanoes, total natural emissions could rise significantly.

The findings also underscored the urgency of technological advancement. Co-author Mike Burton stated, “High-frequency, high-sensitivity sensors open new frontiers in volcano monitoring,” offering improved eruption forecasting and safety for communities near active sites. The team aims to adapt the technology for drones, enabling safer exploration of hazardous zones.

Uncharted territory: 19,325 seamounts found

Meanwhile, a SOEST-led study, published in Earth and Space Science, utilized radar satellite data to identify 19,325 previously unknown seamounts—undersea volcanoes—bringing the global total to over 43,000. Over 27,000 remain uncharted, as only 25% of the seafloor has been mapped via sonar.

These seamounts, which range from 1,100 meters tall, are “potential CO? sources” and play a key role in ocean dynamics. “Seamounts’ ‘wake vortices’ drive deep-water upwelling,” explained researcher Jonathan Gula, redistributing heat and carbon. While underwater eruptions may not rival human emissions, their accumulation and interaction with ocean currents could amplify natural carbon flux.

Paul Wessel, an author on the seamount study, likened the discovery to uncovering critical infrastructure: “They’re oases for biodiversity” and vital for climate models. The findings also sharpen debates over deep-sea mining and global marine protection, as seamounts host unique ecosystems.

Natural carbon’s role in the spotlight

The studies converge to complicate the anthropogenic climate narrative. Current estimates attribute roughly 90% of modern atmospheric CO? increases to human activities, but revised volcanic emissions and unquantified seamount contributions may suggest a higher “natural baseline.”

Riddell’s team suggests global volcanic CO? could rise from 0.26 gigatons annually to over 0.78 gigatons—still dwarfed by 35 gigatons from fossil fuels—but such adjustments force a reckoning. “The certainty of attribution just took a hit,” says climate critic Anthony Watts, echoing calls for humility in climate science.

Historically, volcanic CO? accounting relied on imperfect methods, prioritizing easily detectable gases. Now, scientists must recalibrate to include hidden hydrothermal systems and vast seamount networks reshaping carbon sinks and sources.

A new era of climate accountability

These studies militate for a reckoning with scientific limits. “We need better data,” Riddell argued—a plea amplified by the call for high-resolution ocean mapping under initiatives like Seabed 2030. While human-driven emissions remain the predominant driver of climate change, the interplay of natural processes is increasingly fraught with uncertainty.

As volcanic systems and seamount networks reveal themselves as underappreciated carbon actors, the world faces a dual task: protecting vulnerable coastal zones and reengineering climate mitigation strategies. “If we’ve been missing this much, what else are we blind to?” asked David Sandwell of SOEST. For now, the message is clear: Nature’s balance sheet demands a new audit.

Sources for this article include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

carbon dioxide, carbon emissions, Climate, cool science, Ecology, environ, hydrogen chloride, ocean health, sulfur dioxide, volcanic emissions, volcanos

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 ENVIRON NEWS